This fall, Contra Viento asked Zoë Erickson and Lucas Foglia to talk about their work and practice. Both make photographs set in the American West, and both are especially drawn to portraiture as a means to exploring its landscapes, industries, and traditions.

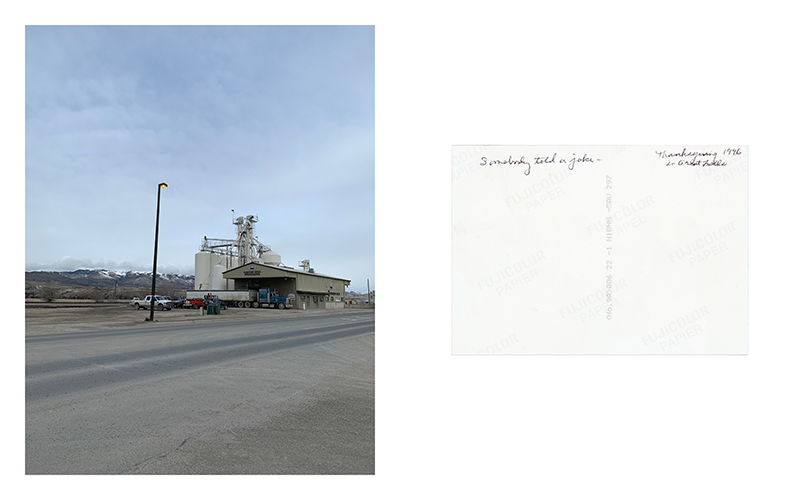

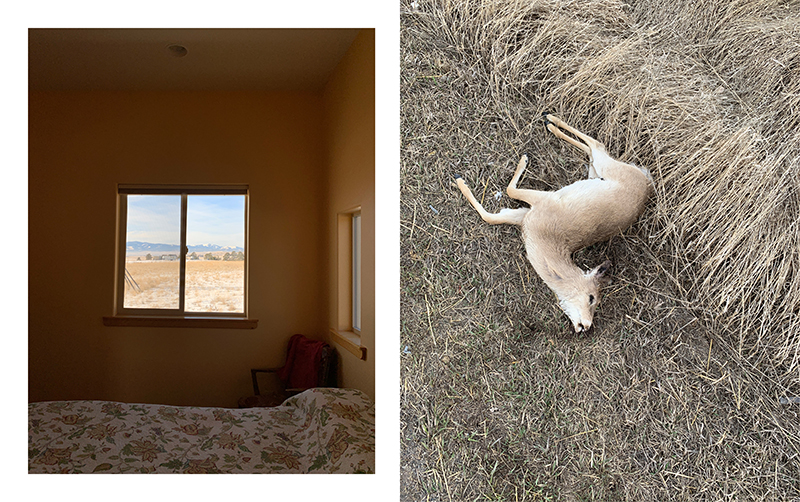

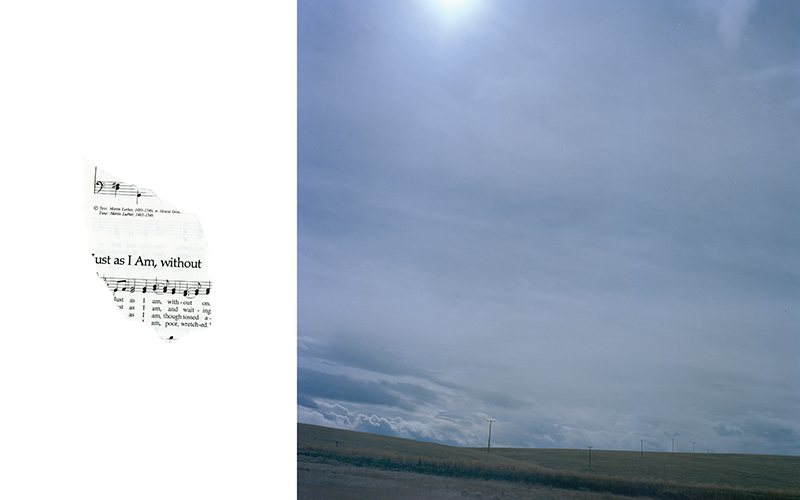

Erickson grew up in Helena, Montana, and is a graduate of Montana State University, where she received a degree in photography. “I’m interested in that space between town and country, between developed and not, between the imagined West and the real-life experiences in actual towns or in actual wilderness,” she says. “My projects tend to be partly autobiographical, and this one in particular is about my experience growing up in this complicated scene: living in town but being surrounded by traditional labor and ideals.”

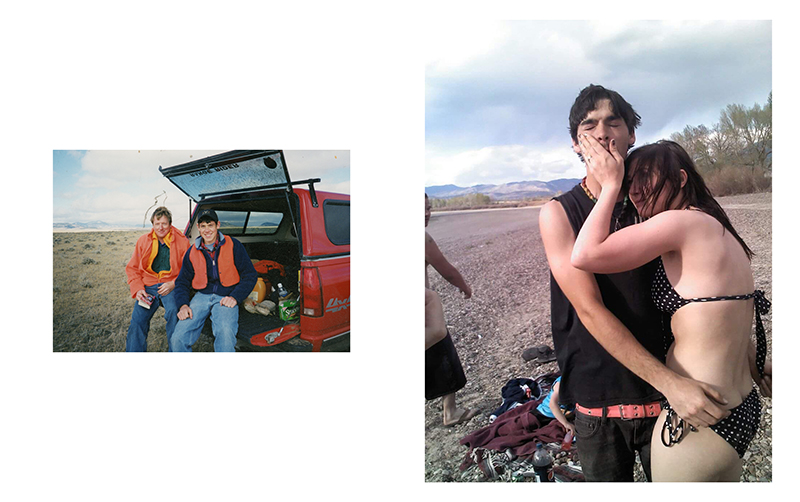

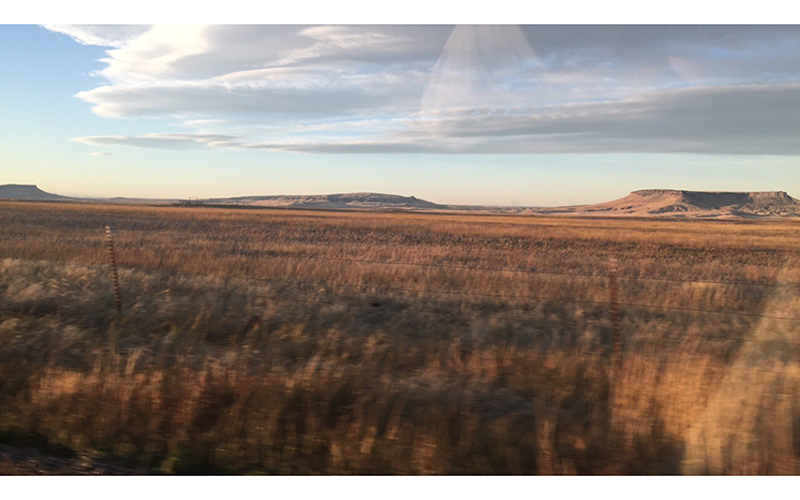

Foglia is the author of three books of photography, including Human Nature and Frontcountry. His work has been exhibited across the US and Europe, and is held in multiple permanent collections. “With Frontcountry,” he tells Erickson, “I wanted to bring people’s attention to the mining boom of the American West. To grab people’s attention, I tried to hook into the myths of the region. I aimed to contrast how mining impacts the landscape with more identifiable stereotypes of ranching and wilderness.”

Their transcript has been edited and condensed for clarity.

•

Zoë Erickson: How did you first begin to photograph? What drew you to photography in the beginning, or when did you first start to realize that photography would be important to you?

Lucas Foglia: The first time I began to photograph was at a summer camp when I was fifteen. I had gone through a breakup when I was fourteen, the year before, at the same camp, with a girl named Jenny, and she stopped talking to me. When I went back the next year, when I was fifteen, it was only Jenny and her friends at the summer camp.

ZE: Oh no.

LF: And none of them talked to me and I felt very depressed and quit the summer camp and came home to my family’s farm on Long Island, where I was hanging around, helping my parents, but also feeling sad. And my mom gave me a camera and said, “Just go and take pictures.” So I borrowed my dad’s camera when I was fifteen. I liked it, it was really fun, and later, when I was eighteen, I got a really old, beat-up Hasselblad from my great-uncle. I did a work-study program and took a class and made some portraits, and then Arnold Newman, the portrait photographer, saw those pictures and asked me to come to his studio in New York. And I started printing at his studio, and other people started seeing that, and it all became more of an identity in college, because I had this relationship with this older artist in New York. I was at least, by then, more confident in the pictures — enough to go out and start my own projects, to show my own identity.

ZE: Right. And to stand by it.

LF: Right. But the model of what I do now came when I graduated from Brown, because I had just done so many of my own projects that no one would give me a thesis show. Like, I hadn’t taken enough visual art classes to be in the visual art department. I had spent years photographing refugees farming on abandoned properties, in empty lots, in poor areas of Providence. So I walked into City Hall and asked the mayor’s secretary if I could use the walls of City Hall for an exhibition. And she asked the mayor and they both said yes, but we have no money for you. And then with some advice from a man named Paul Brooks, who was the mayor’s officer of protocol, I asked the mayor if I could use his name as the honorary chair of my exhibition at City Hall. And the mayor said yes. (He’s now in the House of Representatives, actually.) So I called the senators’ offices and said the mayor is supporting an art exhibition in City Hall about refugees, will you support it too? And the two senators supported it. Then I wrote a grant saying I had a project that was supported by the two senators and the mayor, which put me on the fast track for an art exhibit at City Hall. I had also partnered with a nonprofit called the Southside Community Land Trust that helped build community gardens in the city. The result of my show and the partnership was that the city gave more support to community gardens, the nonprofit organization secured more funding for their work, gardeners felt there was dignity in the pictures, and through all that I met an art collector who started talking me through how to edition prints and sell them, and who introduced me to museum curators and gallerists. I was able to focus on making art because of that support.

ZE: Is that kind of social impact and change, to the benefit of your subjects, the result you hope for in your current projects as well?

LF: With Frontcountry, I wanted to bring people’s attention to the mining boom of the American West. To grab people’s attention, I tried to hook into the myths of the region. I aimed to contrast how mining impacts the landscape with more identifiable stereotypes of ranching and wilderness. Along the way, I gave copies of my photographs back to people I photographed. I also gave copies to nonprofit organizations that were working to preserve land or combat the policies that allow for irresponsible mining or drilling practices.

ZE: Do you have some insight into how the subjects of your images react to those policies, like those responsible for poor mining practices and fracking? For ranchers who are more representative of the traditional Western lifestyle — are they conscious or worried about these potential policy changes, or are they comfortable with it?

LF: The tricky thing I discovered is that land in the Mountain West is mostly seen as a resource by people who live there. On the coast, people like to talk about the precipice that we’re on, in terms of climate change. In the West, people living in small towns tend to feel small in relationship to the scale of the landscape. So land feels big. Because it feels big, it feels like it’s useable. And in that sense ranching is still extracting from the landscape and mining is extracting from the landscape, but they’re two very different things. Ranching has a tremendous impact on climate, in the aggregate, and also a local impact in terms of riparian systems. Mining has a tremendous impact on the landscape in terms of the actual local development, and the exhaust from the gas or the oil or coal that’s burned. So it’s a daunting project.

ZE: Definitely.

LF: I think that at most, for the scale of those economic incentives, I made some people more aware of what following those economic incentives can do to a landscape that’s famous for being wild.

ZE: I grew up in Helena, Montana, and as much as I’ve thought about these things, I haven’t thought about that comparison — how land in the West can feel more endless, whereas on the coast you’re confronted with limits. My father grew up in Libby, Montana, in the northwest corner of the state, in the 1970s. Libby is the site of the W.R. Grace and Company vermiculite mine, which is famous for getting a lot of people sick with asbestos poisoning, including my dad and three of his five brothers. My dad worked as a logger when he was young, but he and his brothers worked hard in school and were able to leave for college on scholarships. Leaving is pretty uncommon for people from that area and of that generation. Most people from the county stayed there, but many of them have been forced to leave in the last decade because of mine closures. And in spite of everything that happened, most of them are still extremely politically conservative, especially regarding ecological and environmental issues. They blame those who are ecologically concerned (or, as my dad says, protected species like the grizzly and the bull trout) for upsetting their livelihoods, and yet many of them are dying from the effects of the industries that once supported them.

LF: Well, a lot of rural areas are also guided by this feeling of freedom. I mean, arguably that’s a false feeling, but it’s some feeling of meritocracy. So any kind of provision of environmental policy is a limitation of that freedom. Until that core narrative changes — not to say that we can change it — there’s still going to be that antagonism that’s really hard to work with, as it then trickles upwards into government.

ZE: Bozeman, where I live now, is one of the fastest-growing cities in the US with a wide mix of mindsets. There’s a lot of farming and ranching people with traditional Western values, but there are also people from all over the country who have moved here. And they’re coming for a type of freedom too, the type in which people want to have this outdoorsy lifestyle: They want to climb and hike and bike and fish. It’s strange because it doesn’t seem to me like many people share the kind of worry that I have while watching the Gallatin Valley’s farmland get eaten up by suburban development and fields of condos. It’s bizarre to drive along a new four-lane road past a family farm with a big “Free-To-Be-Moved” sign on the side of the house, and all these sad-looking cows next to the highway, and then surrounding every border are these cookie-cutter houses.

LF: Yeah. I actually photographed one of these last families, on their family farm in Jackson, Wyoming, where a similar metaphor surfaced for me. I photographed a local schoolteacher helping this family shoot a cow.

ZE: I remember that one.

LF: What you’re pointing to is a problem I see with a lot of my friends who love nature. They go to nature because they love it and want to conserve it, yet their use also impacts it. But the scale of impact from recreational use is much, much smaller than ranching or mining. So the first thing we can do is change the story. And I actually, for the record, believe that there’s art in storytelling and that there’s room for stories in art — but a lot of journalists are poking at the cracks of the world. And it’s really easy to make a story about the negative aspects of mining, or driving, or developing wilderness, or ranching, or anything in-between in the rural West. But what I think we need more of are those stories of what these landscapes could be. Because then we have an image to grow into.

ZE: Do you think this rural West — the way that the West has been, traditionally and culturally, and in some places still is — will continue to be pushed to the wildest corners? Will all these developments keep swallowing it up, or can it continue to exist?

LF: I think it will continue to move through social and economic trends. For example, I was following up on the Frontcountry series last year in Arizona, where the state has a loophole in which a farmer, if they dig a well, has no limit on the amount of water they can pull from that well. And in response to the drought in California and elsewhere, some very large and largely corporate farms have opened up and put in incredibly large pivot irrigation systems for corn in the desert, which then goes to feed cows. So they’re draining the water that’s under the desert to feed the corn to feed the cows.

ZE: It sounds like an environmental nightmare.

LF: Arguably, it is. That’s based on one policy loophole. If that one policy loophole changes, the farms change, the landscape changes. All you have left is a relic of that past policy. And all across the West I see scars from previous attempts. Today I drove past this incredible network of natural gas wells, all across New Mexico, and I remembered seeing wells being drilled in Wyoming when I was working on Frontcountry. And now they’re installed, and they’re less imposing because you don’t see the towering drills. You just see these green and brown containers and pipes running along the landscape. What I wish for the West — and what I see the potential for — is a smarter use of resources. There is potential for large-scale renewable energy and installations of the machinery necessary to produce renewable energy. And if that technology evolves it can allow for nature to live with it.

ZE: Absolutely.

LF: And I see a potential for larger conservation areas, rehabilitation areas, which, if the infrastructure is approved and funded to get people there through public, efficient transportation lines, would allow those people to appreciate those places and experience them and grow to love them in a sustainable way. Both of those things are possible, in our generation.

ZE: You think the opinions are changing, people are becoming more accepting?

LF: Locally, yes! One of the teenagers I became friends with in Wyoming grew up to have a business where he would take people mountain lion spotting, and he made more money than any of his family made working in the natural gas fields or farming or ranching. He put a board over a creek near his family’s house, and mountain lions are smart enough to not get their feet wet in the cold, so he would have a dog just follow the scent straight from that board over the creek, to be able to reliably track the mountain lions in the forest near his house.

ZE: That’s beautiful.

LF: It’s a small story, but in the midst of big industries.

ZE: I’m interested to see what happens in places across Montana that appear set to expand with development — all these medium-sized towns where there’s now a mix of backgrounds and careers, where you see these small epicenters surrounded by more rural lifestyles. My projects tend to be partly autobiographical, and this one in particular is about my experience growing up in this complicated scene: living in town but being surrounded by traditional labor and ideals, and also being influenced by the more romantic images of the West. I’m interested in that space between town and country, between developed and not, between the imagined West and the real-life experiences in actual towns or in actual wilderness populated by ranch lands.

As an example of something that I see in this in-between space, my family used the play what we called the eight-second game on the trampoline. My dad would pretend to be a ‘bucking bronco,’ which, if you fell off before eight seconds were up, would somehow transition into a bull and gore you, like with little finger horns. We were playing rodeo, on the trampoline, in downtown Helena. It’s this melding of conventional Western culture and modern life. I’m wondering what kind of experiences you encountered while photographing Frontcountry that surprised you, in terms of what you learned about more traditional people’s approaches to modern lifestyles.

LF: Let’s look at your family, and your pictures around your family. I’d say, if the project doesn’t work, no one’s going to care about your family. If the project is good, people will care about your family. And if the project is great, people will look at the pictures of your family and think about their own families. They’ll see it in terms of their own life. And that’s the challenge. I grew up on a farm in New York and as I was growing up the neighbors sold their land and there were suburban houses built that had views of my family’s farm. So on a microscale, what I saw as a kid, mirrored what I see in the rural West.

ZE: Sure. That’s what I’m seeing in the rural West as well. How do you first approach someone to photograph? How do most of these relationships begin?

LF: With the photograph we talked about before, of the cow being shot, I got lost on a dead-end road and at the end of the road was a family’s house, and I walked up and said, “Hi, I’m Lucas.” And they recognized me from the church service I’d gone to the weekend before, because another rancher had invited me to go to church with him. I also knew a friend of theirs, from getting up really early in the morning and going to where people gather for coffee. Usually I find that a church, a coffee place, or a dance hall is the best place to meet people in a small town.

ZE: Right. Those are the community centers.

LF: And I described my project in one sentence that was relatable. I said, “I’m interested in making a story about the jobs that allow people to live in a landscape that’s famous for being wild.”

ZE: And people respond to that.

LF: I probably didn’t use the word landscape. I just thought, like, the jobs that allow people to live in the wild West.

ZE: I admire your work for its ability to communicate that feeling of honesty and authenticity — the photographs feel like they’re stemming from a mutual appreciation between you and your subjects.

LF: The vast majority of people I meet have a world that makes sense to them. Even if they’re working for a mine that, in my mind, is destroying a landscape. They see that work in terms of the support it gives to their family. And I don’t want to discount that. So in the end, my project, as a result of those values we just talked about, is not really an indictment of how ranching or mining is destroying the American West. It’s a portrait of how people live and work in a landscape that’s famous for being wild. And some of the images have been used by organizations for advocacy against unsustainable practices. And all of the images have been given back to communities, and they’re living on people’s walls.

ZE: That’s beautiful. I think if you’re making a true portrait then of course it’s going to have many faces. I suppose you can always take one piece of something and make it into a larger narrative

•••

Zoë Erickson is an artist from Helena, Montana. She photographs the scenes and characters of her surroundings, often suggesting uneasy moments and ambiguous emotions. Erickson explores the relationship between the individual and the whole by combining original work with appropriations, drawing heavily from her experiences, and referencing the surrounding culture. Erickson graduated with a BA in photography from Montana State University in Bozeman, Montana.

Lucas Foglia grew up on a small family farm in New York and currently lives in San Francisco. His work focuses on the intersection of human belief systems and the natural world. He recently published his third book of photographs, Human Nature, with Nazraeli Press. Foglia exhibits internationally, and his prints are in notable collections including International Center of Photography, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and Victoria and Albert Museum. He photographs for The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, Bloomberg Businessweek, and others. Foglia also collaborates with non-profit organizations, including Muso Health, The Nature Conservancy, Sierra Club, and Winrock International.